How Datomic made me reconsider data

Recently I’ve been working on a client project whose data paradigm has opened my eyes to a new way to look at and explore data. We’re using a Datomic database, which has compelled me to confront and challenge some of the assumptions I’d previously made about data storage.

Relational Data

For many of us, the idea of a database instantly brings to mind a data store that utilizes a relational model. We think of tables that have relationships to one another using primary keys, and data that can be queried using SQL. We understand data as occupying individual spaces in these tables, and we navigate specifically to those places in memory whenever we want to access, delete, or change data. For example, I may have a contacts table that looks like this:

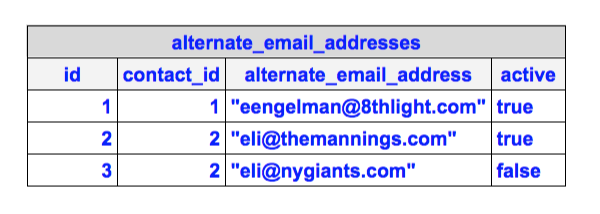

It’s possible that some of our contacts have several email addresses that they’d like to share with us. Let’s create another table called alternate_email_addresses to store this information, if we have it. We can link the contact to their alternate_email_address by including the contact_id in this table:

We can query for Eli Manning’s alternate email address(es) using the following SQL statement:

SELECT *

FROM alternate_email_addresses

WHERE contact_id=2;

Now, let’s pretend that Eli decided to quit football, leave the New York Giants, and start a software apprenticeship at 8th Light. We will need to change his primary email address in our database from “eli@nygiants.com” to “eli@8thlight.com,” since his New York Giants email address will presumably be deactivated.

UPDATE contacts

SET primary_email_address='eli@8thlight.com'

WHERE contact_id=2;

As you’ll notice, after changing Eli’s primary_email_address, we no longer have record that this email address was ever “eli@nygiants.com.” We could have moved it to the alternate_email_addresses table. However, because this email address has been deactivated, we would want to add a flag to that table to identify deactivated email addresses.

This change may require some other data cleanup: we would probably want to indicate that all of the other records in alternate_email_addresses are still active. This could get tricky depending on how many contacts we have. And all of this effort is just to save the fact that Eli used to have a different email_address. This information may never be needed again… But what if it is?

Let’s take a little break from our New York Giants (there are some weeks when many of us fans sure want to!) to talk about Datomic and how it helps us address that question.

Datomic

Datomic is a distributed database that uses a logical query language called Datalog. Rich Hickey's Intro to Datomic video is a great overview of the rationale, architecture, and mechanics of Datomic, and I highly recommend viewing it if you’re interested in learning more. For now, I’ll give a brief introduction on its three main components: the data store, Peers, and the Transactor.

The data store is unique in that it is external, which allows users to persist their data in anything from a SQL system such as Postgres to a NoSQL service such as Amazon DynamoDB. The Datomic team reasoned that storing data is a problem that computing has already solved, so they focused on other challenges, like handling reads and writes.

A Peer is any application that includes the Datomic Peer Library. These Peers have the ability to query data within the application, communicate with other elements of the system (Transactor and data store), and also represent a partial copy of the database through caching. Because our application is able to query its local memory, each application instance has the ability to interact with the dataset independently.

The Transactor is separate from both of these components. Its sole responsibilities are to write information to the data store, and then alert its Peers about new data updates. It ensures that all data remains ACID compliant.

This three-part architecture has a lot of interesting implications, and there’s a lot of potential for really cool and exciting innovations in the future.

However, I can’t wait any longer to mention my favorite, and perhaps most mind-bending part about Datomic: all data in Datomic is immutable. This means that each element of data can never be changed, and is never deleted!

Immutability

The main tenant of Datomic is that it never forgets. In Rich Hickey’s Intro to Datomic video, he likens Datomic to the method of record keeping that has been used for hundreds of years, before computers or databases. Facts were written down on paper—on hanging wall calendars, or in address books—and each new piece of information that needed to be recorded would simply be added. Existing data would never be overwritten or erased.

I understand that you’re probably dying to see how this immutability can be helpful, and how it can even work in a large-scale production application that ever needs to edit data. Why would we want to go back in time to an older way of recording data?

In relational databases, we often overwrite our existing records with new information. We saw this in our example with Eli Manning’s email address. In order to represent that Eli’s primary_email_address is now “eli@8thlight.com,” we had to lose the fact that it was once “eli@nygiants.com” by overwriting it with the new data. This idea of “new information replaces old” originated when disk space was expensive, and computers didn’t have any to spare. Data is saved to a specific place, and then recovered via a pointer. We remove old information with the assumption (or the hope) that we’ll never need it again, and this allows us to add new data without eating up additional disk space.

Nowadays, though, disk space is plentiful, and we can afford to save everything.

Rather than organizing data in a series of boxes (or relational tables) that are stored in a particular place, Datomic databases can be thought of as a ledger of facts that are written at a particular time. Whenever we write to the data store, we’re adding a new set of facts that we want to be able to look back to and remember.

Every transaction written by the Transactor is put in a new place in memory, and is given a timestamp that connects it to a specific transaction. The implication of knowing which transaction added which piece of data means that we are able to easily access all of our data as-of any point in time, or even within a window of time.

As we’ll soon see, we don’t need to worry about losing Eli’s email address from his days in the NFL, because we can always query our database as-of a time before his 8th Light apprenticeship, when he was still throwing touchdowns for the Giants.

The Datom

Datomic’s one and only data structure is the Datom. That’s right: Every piece of data in Datomic fits the definition of a Datom. As per the official Datomic glossary, that definition of a Datom is:

An atomic fact in a database, composed of entity/attribute/value/transaction/added.

For those of us whose brains are accustomed to thinking of data in rows and columns, we can correlate a Datom to a row, and a Datom’s attribute to a column.

Let’s take a look at how Eli Manning’s information may be stored in a Datomic database comprised of several Datoms.

We have one Datom for each attribute that makes up Eli’s contact entity. This entity itself is represented by a unique entity-id, 2, which is generated by the Transactor.

Let’s go back to our example of replacing Eli’s New York Giants email address with a brand new 8th Light one. In Datomic, it is possible to define attributes with varying cardinality so that they can be associated with just one value, or with multiple values. This means that the idea of an alternate, or additional email address, is already built in. We’ll touch on this a little more soon, but for now let’s take a look at the new fact that we would write in our database to represent replacing both of Eli’s email addresses:

Notice that:

- We have the same entity number, because we’re still working with Eli’s contact entity.

-

We include the attribute we’re editing,

:contact/email-addresses. -

The value of that attribute is what we’re changing, so notice how we still include the “eli@themannings.com” address, but we change the other one. This allows us to say that these are both of Eli’s current

email-addressesas of transaction 1001. -

Like we mentioned before, if we want to see what Eli's

email-addresseswereas-oftransaction 1000, or 999, or 1, we could do that at any time.

In the column farthest to the right, we have our “added” component of the Datom, which is true for all of these Datoms. We’re also able to retract a fact if it is no longer true for an entity. To illustrate this, let’s suppose that Eli decides to go off the grid entirely and deactivate both of his current email-addresses. To reflect this in our database, we would want to add a new Datom that says that these email-addresses are now false.

To Schema, or not to Schema

Datomic does utilize a schema, though it differs from what we typically think about with traditional relational schemas. A Datomic schema describes specific characteristics of attributes, but doesn’t necessarily need to limit those attributes to a specific type of entity—this can be done in the application code. Defining an attribute requires three pieces: the unique identifier (or name) of the attribute (:db/ident), the type (:db/type), and the cardinality (:db/cardinality). You can see that even Datomic’s built-in attributes follow this structure: the identifier of each (:db/ident, :db/type, :db/cardinality) is defined under the :db namespace.

For our contact database, we may create a schema defining three attributes:

Although it is not essential to include a namespace for each attribute that matches up to their entity, it does help to avoid name collisions, and also helps to communicate the intent of each attribute. In this schema, we are expressing that we’re setting our database up for a contact entity with three attributes.

Benefits & Challenges

The benefits of implementing a looser structure in our data allows us to be adaptable to almost anything that our ever-changing requirements may throw at us. With Datomic, we are not bound by a rigid structure of existing tables, relationships, and keys.

The beauty of the Datom being fairly generic is that it’s also ubiquitous. We can use it for any entity use case that comes our way. What if Eli’s big brother Peyton also decides that he wants to join 8th Light, but instead of supplying his email addresses he gives us several phone numbers? We could easily accommodate this with our loosely structured Datomic database. We would need to add a :contact/phone-numbers attribute to our schema:

Then we would simply add a Peyton entity and associate the attributes that are pertinent to him, without having to worry about the mismatch in data between the two contact entities (email-addresses vs. phone-numbers).

And we're good to go!

The possibilities for extensibility are endless! Going further (or maybe a little bit too far), we could even start recording details about each of the Super Bowls that every new 8th Light apprentice has won. Again, we wouldn’t have to worry about the fact that most incoming 8th Lights do not, in fact, have a Super Bowl ring. Yet we could easily still add this attribute to both of the Manning entities.

Conclusion

Perhaps this is a lesson that we can bring into our development of systems that use a relational model. Why should we shy away from adding more data that is useful to our application just because our current structure of tables isn’t set up for it? After exploring Datomic’s ability to allow us to be flexible, adaptable, and agile, I am encouraged to continually seek out more creative ways to represent data.

It is worth mentioning that Datomic is still a relatively new technology, which brings about its own set of challenges. It is still evolving, and as such, there aren’t always a plethora of resources online. It’s often difficult to find more than a few Stack Overflow entries, blog posts, and tutorials to assist, besides Datomic’s own documentation. However, in lots of Googling, I have noticed that Rich Hickey himself is very active in answering questions on both Stack Overflow and even a Google Group dedicated to Datomic, which is cool and encouraging. There are several early adopters who are using Datomic in production in addition to my current client—so though Datomic is new, it is production-ready and the community surrounding it is supportive and growing.

Sometimes it can feel like you’re the first one to ever try to query data in a particular way—which can be daunting. But honestly, the opportunity to think about data in a new and different way makes it worth it. Understanding data in a linear/time-sensitive way—instead of relationally—is eye-opening. It’s helped me to understand my data more thoroughly, and also realize new, creative ways that data can be linked and understood. We’re not always restricted by the database structure that we currently have—and this allows us to add even more relationships between our data.